Mindsparks — The Phenomenology and Wonder of Sudden Insight

Of Neurons, Firelight, and the Mystery of the Mind

I find myself in a particularly creative state. Ideas arrive fast and furious. Connections spark between seemingly unrelated concepts. Words pour out as if of their own accord. Time itself fades into the far distance — I am in Flow.

Mindsparks.

A wood fire on a cold Michigan winter evening. No lights save the glow of the fireplace. A comfortable chair by the hearth. Suddenly — crack! — a spark leaps from the logs, luminous in its brief arc, then gone. Silence returns.

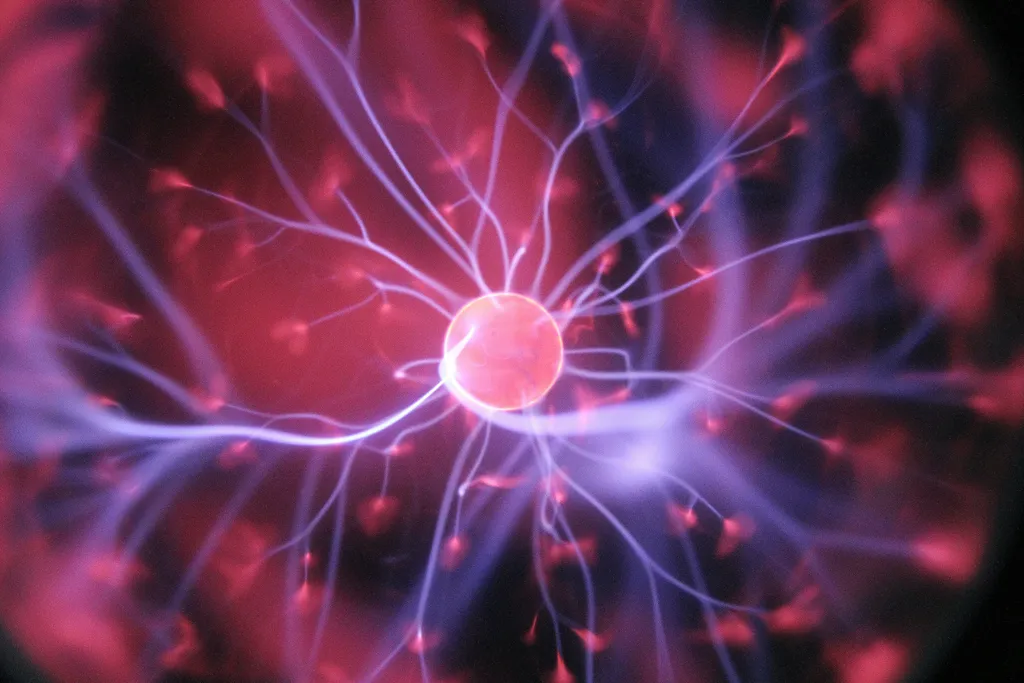

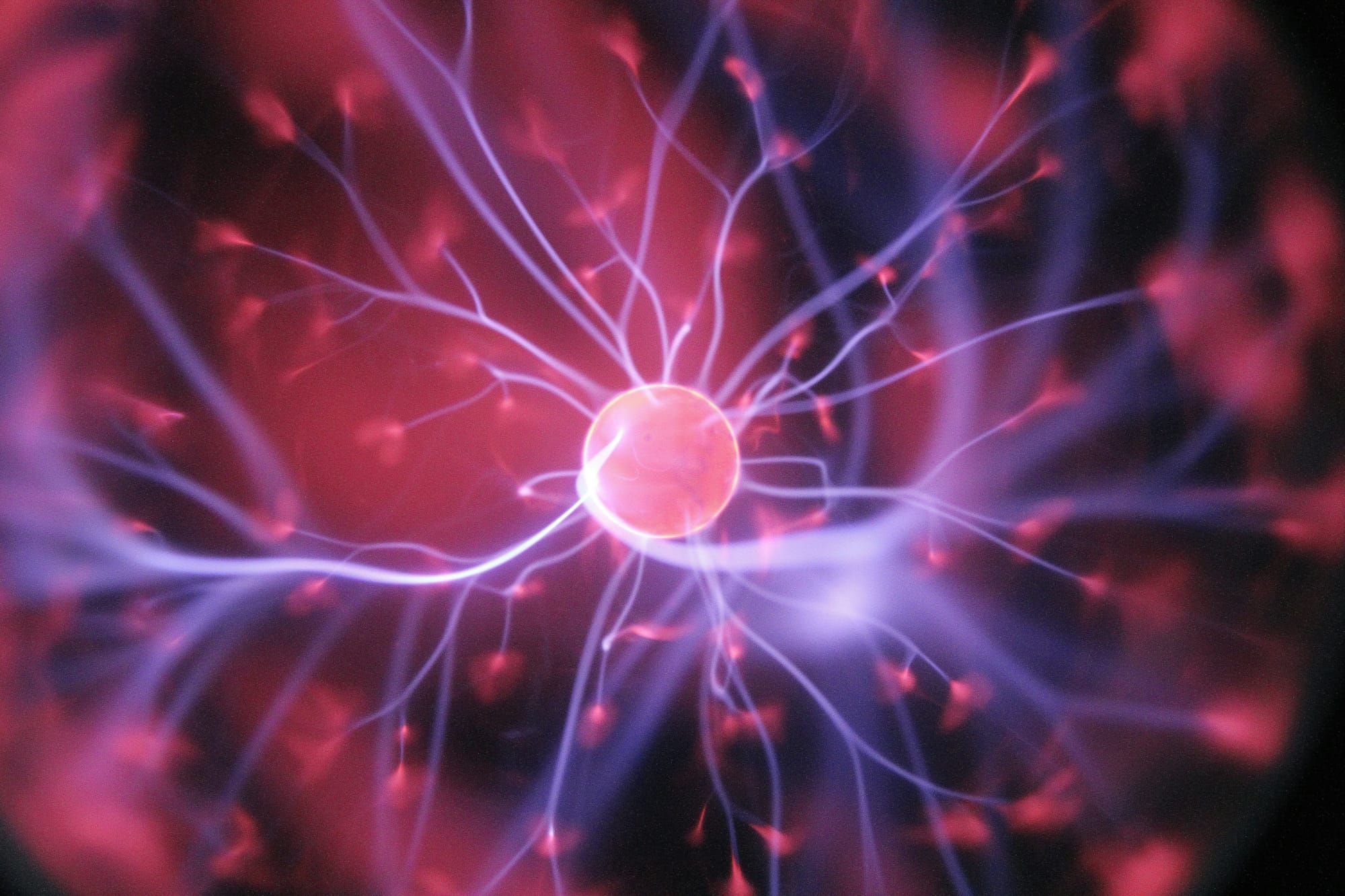

Somewhere in the mind, a neuron fires. An electron jumps energy levels. A photon bursts forth, brilliant for an instant, and then — like the fire’s spark — it is gone.

This moment leads me to wonder about the whys and hows of spontaneous cognition.

Spontaneous Cognition

A sudden emergence of insight that presents unexpected ideas, solutions, connections, or reinterpretations — producing a response that is non-obvious, original, and often feels as though it arrived unbidden. It usually occurs off-task, when conscious focus is directed elsewhere.

Neural Mechanism — The Default Mode Network (DMN)

The DMN coordinates background mental activity — the unconscious connecting and processing that happens when we’re not focused on specific tasks. It is a group of interconnected regions in the brain, including parts of the prefrontal cortex, the precuneus (near the upper part of the parietal lobe), the posterior cingulate cortex, and portions of both the parietal and temporal lobes.

Intriguingly, the DMN shows reduced activity when we are engaged in tasks that require focused attention. It becomes most active during rest, daydreaming, and mind-wandering — mental states often undervalued as unproductive. In fact, this is when the DMN links distant concepts and draws on memory to form new associations. It’s the likely stage on which mindsparks first take shape.

Incubation Effect

Insights often occur when attention shifts away from a problem — showering, walking, or simply staring into a fire. This “off-task” state appears to allow unconscious processing to connect ideas without the constraints of conscious focus.

A classic example is the dream of German chemist August Kekulé. Struggling to determine the atomic structure of benzene, he could not see how its six carbon atoms might be arranged. One night, he dreamt of a snake seizing its own tail — an image that crystallized into the realization of a ring-shaped molecule. Upon waking, he realized that benzene’s carbon atoms formed a closed hexagonal ring, a breakthrough that became one of chemistry’s foundational structures.

The similar story of Archimedes’ insight is very well known. Less famous is the account of mathematician Henri Poincaré, described in his 1908 book Science and Method. While stepping onto a bus during a geologic excursion, Poincaré experienced a sudden flash of realization — “without anything in my former thoughts seeming to have paved the way for it” — that the transformations he had been studying were identical to those of non-Euclidean geometry. It was a tremendous leap of insight, one that would later find applications in cryptography and mathematical physics.

That moment of effortless clarity came only after he had set the problem aside — when it was no longer in the front of his mind.

Neural Spark

EEG studies reveal a burst of gamma waves — electrical activity with frequencies ranging from 30 to 100 Hz — in the right temporal lobe roughly 300 milliseconds before an insight reaches conscious awareness — literally a neural “spark.” This fleeting surge appears to mark the brain’s sudden integration of disparate elements into a coherent whole, the final step before the idea bursts into consciousness.

The Phenomenology of Mindsparks

You’re not working. Not really. Your attention is elsewhere — watching a fire, walking down a quiet street, rinsing a coffee cup. Then, without warning, it arrives.

A connection flashes between two ideas that previously seemed light-years apart. A new solution takes shape in perfect form and structure. Or an old problem suddenly rearranges itself into a simpler, more elegant form.

In that moment, there is no labor — only emergence. No conscious scaffolding — only the completed structure, whole and ready. The mind’s background hum falls away, replaced by a bright stillness.

It feels less like thinking and more like receiving. The idea arrives with the same inevitability as a spark leaping from a log on a winter night — born of deep combustion, yet impossible to predict. It’s the electron’s sudden jump, the photon’s brief blaze, the moment in Kekulé’s dream when the snake seizes its tail.

And then, as quickly as it came, the spark fades into memory. What remains is the afterglow — the quiet joy of having touched, however briefly, the edge of mystery, and perhaps the depth of stillness.

Science and Reductionism

Science gives us a precise map of what happens before an insight — the DMN’s quiet hum, the incubation period, the gamma-wave ignition. But the lived experience is something else entirely: not a diagram, but a spark; not a wave frequency, but a moment of astonishment. Both views are true, yet neither is complete without the other. The map tells us where the paths run; the phenomenology reminds us why we walk them.

Yet maps, by their nature, are simplifications. Reductionism seeks to explain by breaking systems down into smaller parts, focusing on components rather than the whole. In Western medicine, for example, we have cardiology, with its often tunneled view into the heart, sometimes to the exclusion of the whole body. Cardiologists typically do not ask patients about their diet, and yet what we eat profoundly impacts the heart and the rest of the body.

This focus is necessary, even essential — specialization can and does save lives. But it is also dangerously easy to get lost in reductionism — to mistake the part for the whole, the model for the reality — and in doing so, to lose the joy of wonder.

Back at the fire, the logs have settled into a deep, slow burn. The earlier sparks are only a memory now, but the warmth remains. I watch as a faint crackle stirs the embers, and another spark leaps briefly into the dark — brilliant, unplanned, gone. Somewhere, deep in the mind’s own quiet combustion, another idea is forming, unseen. Whether it arrives as a gamma-wave surge or as a dream’s sudden image, it will come in its own time.

We can trace the pathways, name the brain regions, measure the frequencies. But the mystery remains, and perhaps it always should. For it is in that mystery that both science and wonder meet — in the luminous instant when the unseen becomes seen, and the mind is set ablaze.

Understanding the mechanisms does not have to kill the magic — indeed, it can deepen it.

Crackling winter flame —

A spark arcs into silence.

Thought is born mid-dark.

Your Turn

Have you ever experienced a memorable mindspark — a sudden flash of insight that arrived unbidden? Where were you, and what were you doing when it struck? Was it a quiet moment by a fire, a walk outdoors, or something entirely unexpected? Share your story — I’d love to hear how wonder finds its way to you. Please feel welcome to share your reflections publicly in the comments or privately via email at: undoing_raaj (at) proton (dot) me.

With gratitude to Hal Gatewood on Unsplash for the image.